In Korean art and culture, two different types of “monsters” are often seen—Nathwi Masks and Dokkaebi. Although the two types have very different meanings, they are both examples of an image that is unique to Korean folk art—the smiling beast. Probably going back to animist/Shaminist belief in a world of spirits that inhabit all aspects of nature and all everyday objects, Korea’s smiling beasts serve to protect, reward, and remind humans how to behave. Although, traditionally, Koreans believed these powers to be very real, they also, on occasion, were able to laugh and call their beliefs nonsense. This duality reflects the complex and lively nature of the Korean heart and mind as expressed in their folk art. And it reflects the affection with which Korea embraces (and perhaps identifies with) its smiling beasts to this day.

Nathwi are typically painted on temples and serve to protect the building and the people in it from evil spirits. With wide noses and flaring nostrils, whiskers, horns, and sharp teeth, Nathwi look very fierce. But they also are usually shown with a big smile, which seems odd for a ferocious protector. And, indeed, Koreans are not afraid of these monsters. Instead, they feel close to them and very grateful for the protection they provide! Single Nathwi usually look straight ahead, but when they occur in pairs, they often look in different directions—all the better to see danger coming!

Nathwi are typically painted on temples and serve to protect the building and the people in it from evil spirits. With wide noses and flaring nostrils, whiskers, horns, and sharp teeth, Nathwi look very fierce. But they also are usually shown with a big smile, which seems odd for a ferocious protector. And, indeed, Koreans are not afraid of these monsters. Instead, they feel close to them and very grateful for the protection they provide! Single Nathwi usually look straight ahead, but when they occur in pairs, they often look in different directions—all the better to see danger coming!

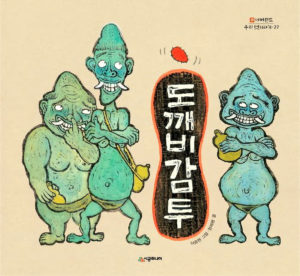

Dokkaebi are ugly, supernatural creatures with long, sharp teeth, horns, bulging eyes, and hairy bodies that have appeared in Korean folk legends since the Three Kingdoms Period (57 BC – 668 AD). Unlike ghosts, which are thought to be the spirits of the dead, Dokkaebi are goblins that are transformed from everyday objects such as trees, chairs or brooms. Korean folklore describes different types of dokkaebi ~ the kind one, the dumb one, one who is “good at fighting and handling weapons, especially arrows,” the one-eyed dokkaebi that eats a lot, and an egg-shaped one who moves by rolling along on the ground.

Dokkaebi are ugly, supernatural creatures with long, sharp teeth, horns, bulging eyes, and hairy bodies that have appeared in Korean folk legends since the Three Kingdoms Period (57 BC – 668 AD). Unlike ghosts, which are thought to be the spirits of the dead, Dokkaebi are goblins that are transformed from everyday objects such as trees, chairs or brooms. Korean folklore describes different types of dokkaebi ~ the kind one, the dumb one, one who is “good at fighting and handling weapons, especially arrows,” the one-eyed dokkaebi that eats a lot, and an egg-shaped one who moves by rolling along on the ground.

Known as pranksters and mischief-makers, they delight in creating havoc. To better move about surreptitiously, they live in sparsely populated areas like thick woods, graveyards and abandoned houses and often appear at night, sometimes wearing a special hat (dokkaebigamtu) that makes them invisible. If a cow is found on the roof of a farmer’s house in the morning, it’s a sure sign that Dokkaebi have been at work!

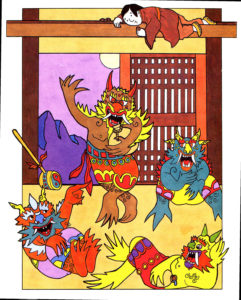

Strong-tempered and bawdy, they like to party with their friends ’til the wee hours, drinking and carousing. Expert wrestlers, they like to challenge travelers to a match for the right to pass. Possessing supernatural powers such as the ability to produce good harvests, large catches of fish, and immense wealth for individuals, Dokkaebi also have some very appealing human characteristics. For example, they are surprisingly trustworthy and always pay their debts on time!

Sometimes called the Robin Hoods of the Korean monster world, Dokkaebi steal from the greedy and give to those who are deserving. Thus, throughout millennia of Korean folklore, Dokkaebi have served as monitors of morality, reinforcing people’s good behavior (sometimes using their big clubs called dokkaebibangmangi like magic wands to conjure up rewards) and punishing them for misbehavior. Yet, throughout their hijinks and shenanigans, there is always at least a hint of a smile on their otherwise ferocious faces!

PS: To see more examples of Korea’s smiling beasts, check out our earlier blog, “Smiling Faces in Lots of Places.”